Sustainable Water - Thomas Ball

Brighton and Hove have been shaped and influenced by water.

Not just through an evolving relationship with the sea, but through the challenges of securing a reliable supply of drinking water and dealing with sewage and the spread of disease during the rapid growth of the 19th Century. The challenges continue today, as population growth, increased water consumption and a changing climate all put pressure on water resources. As a result, Brighton & Hove is classified as an area of ‘serious water stress’. As there are no rivers within Brighton & Hove, the city is entirely reliant on the chalk aquifer that sits beneath it and the Downs for its drinking water. This store of fresh water must be carefully managed and protected to provide a clean and reliable supply. As a coastal city, it must defend itself from the sea and be prepared for more frequent extreme weather events and rising sea levels, while maintaining and improving seawater quality and protecting vulnerable marine life and habitats. The recent designation of a Marine Conservation Zone west of Brighton Marina and the award of UNESCO Biosphere Reserve status to the area are positive steps.

The One Planet Living principle of sustainable water sets high standards to aspire to. Some standards can be met by education and simple changes in behaviour, while others can only be achieved through new technologies and long-term investment in infrastructure.Building on the work of forward-thinking people in the past and with innovative thinking for the future, the city is striving to create a more sustainable relationship with water, in all its forms.

The plant treats over 95m litres of wastewater produced each day by Peacehaven, Telscombe Cliffs, Saltdean, Rottingdean, Ovingdean and Brighton & Hove.

The treated water is pumped out to sea via a new 2.5km sea outfall.

Southern Water must carefully monitor ground water levels so as not to abstract too much water in any one area and to prevent salt water intrusion into boreholes located closer to the sea.

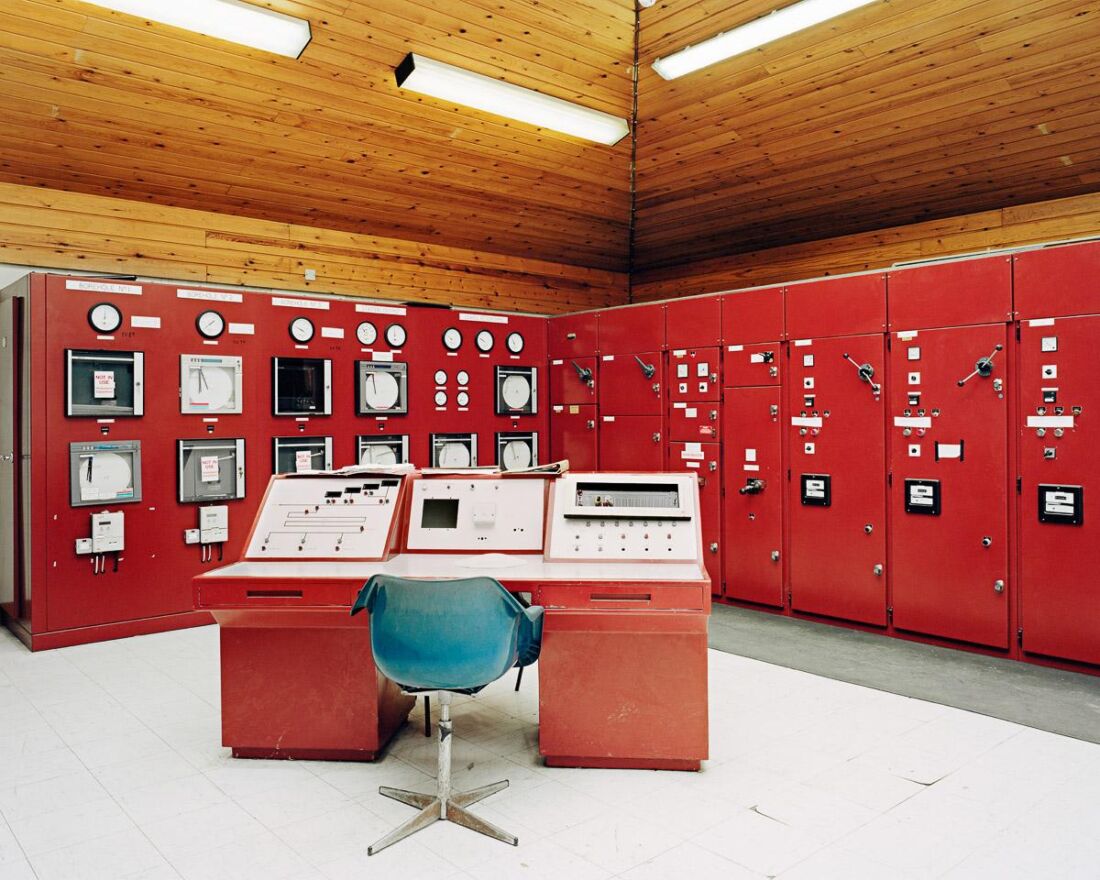

This water supply works and pumping station in East Brighton was built in 1932. It has 3 boreholes that currently supply 12.9m litres per day, just over 10% of Brighton & Hove and the surrounding area’s water.

All the boreholes sit within the main chalk aquifer, and water is abstracted through a system of horizontal tunnels or ‘adits’ – many of which were hand dug – that intercept water flowing through the fractured rock.

These machines monitor and control the output from the borehole. They are linked to a regional control centre so they can be operated remotely.

The sewers are still in use and have an estimated lifespan of 500 years. Sewer tours have been running since 1956 and continue today.

They help educate visitors about where their sewage ends up and about what not to put down their toilets and drains.

When rain fell on the concrete and flint catch, it flowed downhill to a basin at the foot of the hill. The water was filtered through sand and charcoal and then fed into large storage tanks under the grounds of Stanmer House.

Each cottage in Stanmer village also collected rainwater on the roof, which was then filtered and stored for drinking water.

The results were used to create a detailed fertility map, showing the levels of nutrients across the land.

The data was then combined with GPS co-ordinates, so fertiliser can be automatically applied by the tractor at the correct levels, depending on where the soil is nutrient rich or poor.

This then flows downhill to water butts throughout the site from which they water the plants by hand with watering cans and buckets.

The membrane allows water vapour - which cannot carry salts - to diffuse through the pipe walls, while the contaminants are retained within the pipes.

By installing a more efficient flushing system for the venue’s urinals, the Brighton Centre is saving an estimated 13,000 litres of water a day.

Widespread installation of water meters also helps Southern to identify leaks across the system and to reduce water loss.

Similar flood mitigation measures have been constructed in other risk areas, predominantly where the city meets the South Downs.

With the climate changing, sea levels rising and increased frequency and intensity of storms, the existing coastal defences are under increasing threat.

As a result of the study, a programme of future improvements works will be implemented to make the coast defences capable of withstanding a 1 in 200 year storm event.

To manage this, shingle must be periodically replaced at the western end. The role of groynes is to stop shingle moving along at the speed it wants to move, and to accumulate it between groynes, as beaches.

Long and short-snouted seahorses, which are protected by law, can be found in the shallower waters and the subtidal chalk reef.

Behind these walls and beneath the boats, the sheltered marina provides a lagoon environment that supports a diversity of species more typical of deeper water habitats, including several sponge species and short-snouted seahorses.

Work began in 1858, with men digging 24 hours a day by candle light in appalling conditions. It was not until the 16th March 1862 that water was finally reached.

At 1285 feet deep (850 of which are below sea level) this brick-lined well is deeper than the Empire State Building is tall.

Essay approach

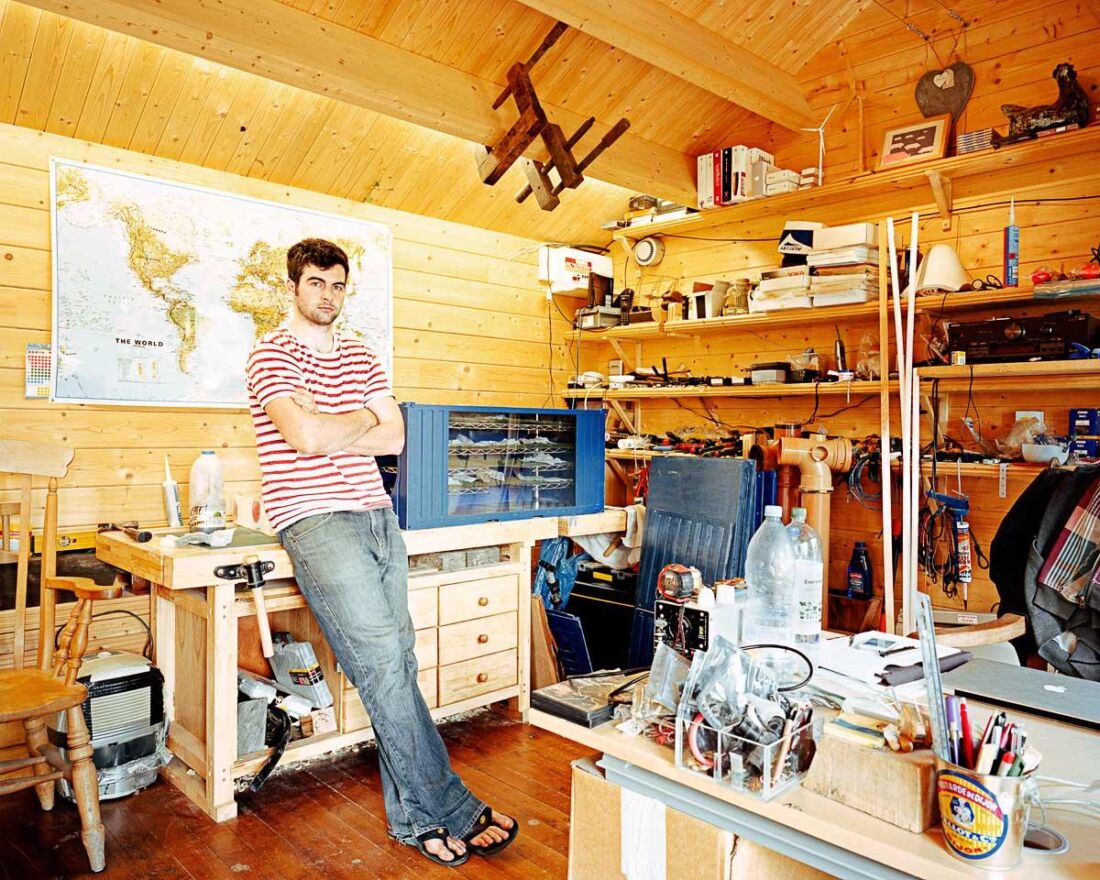

As Brighton & Hove’s seafront is so well known, I have tried to focus my attention away from the more traditional views of the city. With my background in environmental science, I was eager to learn more about the region’s geology and the influence the chalk landscape has had on the city. I also wanted to look into the city’s history and to see what impact past events have had on Brighton and Hove’s relationship with water. My intention has been to form a narrative between history, landscapes, people and infrastructure and highlight some of the ways local residents, businesses and the Council are conserving, protecting and recycling water today.

Like much of my previous documentary work, I shot the majority of this series on a large format 5×4” sheet film camera. The clunky nature of the camera and expense of the film place limitations on the way I can work. Although this can be frustrating, I find these limitations help me to focus on the people, places and topics that I am most interested in and new opportunities and ideas arise as a result.

I have learned a lot about water in Brighton & Hove and the South Downs while working on this series. I have also been reminded about how disconnected many of us are from where our natural resources come from and where our waste ends up. In the case of water, it is important that we constantly remind ourselves what a vital resource it is and that we can’t just take it for granted.